On August 11, 2015, the Superior Court reaffirmed the principle that “all purchasers of property in a subdivision acquire an easement over all platted roads in the subdivision plan.” Starling v. Lake Meade Prop. Owners Ass’n, No. 1779 MDA 2014, 2015 Pa.Super. LEXIS 458, at *12-13 (Pa.Super. Aug. 11, 2015). Because lots are often laid out in a recorded subdivision plan, the ownership and access rights over roads, streets, ways, or other alleys shown on the plan are matters of which both developers, and property owners should be aware. Such rights can affect not only access and use, but also the development of property.

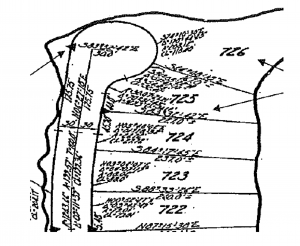

The Starling case involved Lake Mead Property Owners Association, Inc.’s (the “Association”) ownership of a cul-de-sac abutting W. Lowell and Nancy Starling’s (the “Starlings”) lots, all of which formed a peninsula jutting out into Lake Meade in Adams County, Pennsylvania. Id. at *1. The Court included an enlarged portion of the recorded subdivision plan in its opinion:

Id. at *2.

The Lake Meade Subdivision was recorded on January 20, 1967. Id. at *1-2. The Association produced a deed from the developer, dated September 25, 1968, which purported to grant to the Association title to all of the roads in the subdivision. Id. at *2. The Starlings acquired Lots 725 and 726 by deed dated August 12, 2002, to which the arrows on the right of a roadway and cul-de-sac known as Custer Drive point in the above depiction. Id. at *3.

The Starlings filed a complaint asserting that the Association permitted the cul-de-sac to be used for various recreational purposes including fishing, picnicking, sunbathing, socializing, loitering, creating bonfires, and partying, id. at *4, and that such uses were inconsistent with the intended use of Custer Drive for ingress and egress purposes, id. at *7.

The Association responded that it owned Custer Drive by virtue of the 1968 deed from the developer and was free to use it in any manner it wanted. Id. at *7-8. The trial court agreed and granted partial summary judgment for the Association. Id. at *8.

On appeal, the Superior Court “conclude[d] that the trial court committed an error of law in finding that the Association has a fee simple ownership interest in Custer Drive and its cul-de-sac.” Id. at *12. Quoting a Pennsylvania Supreme Court case, the Superior Court explained:

When lots are sold as part of a recorded subdivision plan on which “a street has been plotted by the grantor, the purchasers acquire property rights in the use of the street.” Specifically, all purchasers of property in a subdivision acquire an easement over all platted roads in the subdivision plan. This right is described as ‘an easement of access’ which means the right of ingress and egress to and from the premises of the lot owners. It is a property right appurtenant to the land which cannot be impaired or taken away without compensation.”

Id. at *12-13, quoting Kao v. Haldeman, 728 A.2d 345, 347 (Pa. 1999).

As such, “[t]he developer simply did not own a fee simple interest in the platted roads in the development in 1968, when it purported to grant such an interest to the Association.” Starling, 2015 Pa.Super. LEXIS 458, at *15. Regarding the Association’s use of the cul-de-sac, the Court stated that “the scope of an easement holder’s right to use the easement is limited to the use contemplated when the easement was created.” Id. at *19. The Court reasoned:

Any platted road in a subdivision creates a legal right of ingress and egress in the subdivision owners. One does not use a road for recreational activities such as parties, bonfires, sunbathing, and fishing. There is no recreational right attendant to the easement that Lake Meade Subdivision property owners enjoy over Custer Drive and its cul-de-sac.

Id. at *20.

Therefore, the Superior Court reversed and remanded “for entry of an injunction permanently enjoining use of the entirety of the platted Custer Drive and the entirety of its platted cul-de-sac to any use other than for ingress and egress.” Id. at *27.

Commonly, when a developer records a subdivision plan containing lots and streets, the idea is that the local municipality will eventually assume ownership and responsibility for maintaining the streets through a process called “dedication.” However, the municipality does not always accept dedication of the street. Pennsylvania has a statute on this point:

Any street, lane or alley, laid out by any person or persons in any village or town plot or plan of lots on lands owned by such person or persons in case the same has not been opened to, or used by, the public for twenty-one years next after the laying out of the same, shall be and have no force and effect and shall not be opened, without the consent of the owner or owners of the land on which the same has been, or shall be laid out.

36 P.S. § 1961.

“For purposes of this statute, ‘a street becomes public when it is (1) dedicated to public use and (2) accepted by the municipality.’” Murphy v. Martini, 884 A.2d 262, 265 (Pa.Super. 2005), quoting Leininger v. Trapizona, 645 A.2d 437, 440 n.1 (Pa.Cmwlth. 1994). “If the street is not accepted within 21 years, ‘the land is discharged from such servitude, and the dedicated portion of it has entirely lost its character as a public street.’” Martini, 884 A.2d at 265, quoting Rahn v. Hess, 106 A.2d 461, 463-464 (Pa. 1954).

Under these legal principles, if the street is not dedicated and accepted within twenty-one years, it cannot become a public roadway “without the consent of the owner or owners of the land on which the same has been.” 36 P.S. § 1961. “[T]he ‘owner or owners’ whose consent is required, refers to the abutting lot owners.” Rahn, 106 A.2d at 464. This is because “where the side of a street is called for as a boundary in a deed, the grantee takes title in fee to the center of it, if the grantor had title to that extent, and did not expressly or by clear implication reserve it.” Id. After the statutory twenty-one year period, if the street is not made public, then “the owners of this abutting land take title to the center line of the street.” Martini, 884 A.2d at 266.

However, the expiration of the twenty-one year period does not eliminate the private rights in the street of all other lot owners within the recorded subdivision plan. “While the public easement or right of use in such lanes or alleys is lost as the result of the passage of such time and lack of use, the purely private rights of easement of individual property owners in the plan of lots to use the alley or way is not extinguished.” Riek v. Binnie, 507 A.2d 865, 867 (Pa.Super. 1986). “The fact that a street may not in fact be open (citation omitted) or that there is no acceptance by the municipality of the street as a public road does not affect the continuing private contractual rights of property owners within the plan to use the streets.” Drusedum v. Guernaccini, 380 A.2d 894, 509 (Pa.Super. 1977). Therefore, while the abutting property owners take legal title to the center line of the street after twenty-one years, such ownership is subject to a private easement of access of all property owners within the recorded subdivision plan.

A private easement created by a recorded plan can impede development, see e.g. Elia v. Zoning Hearing Bd., 1 Pa. D & C.3d 393 (Pa.Com.Pl. 1976) aff’d 365 A.2d 189 (Pa.Cmlwth. 1976)(paper street on recorded plan within lot’s dimensional setback prevented issuance of building permit), cause boundary disputes, see e.g. Croyle v. Dellape, 834 A.2d 466 (Pa.Super. 2003)(driveway and fence installed encroached upon 60 foot private right of way as shown on recorded plan although actual right of way significantly narrower), create access disputes, see e.g. Estojak V. Mazsa, 562 A.2d 271 (Pa. 1989)(fence erected between lots to prevent neighbor from using private roadway recorded on plan for ingress and egress through property), or even invite unruly neighbors, see e.g. Sides v. Cleland, 648 A.2d 793 (Pa.Super. 1994) (use of trail through landowner’s property shown on recorded plan to ride motorcycles at high speeds and throw parties).

The Law Firm of Sebring & Associates is experienced in representing property owners and developers throughout the subdivision process and beyond. Please contact us if you have a question regarding any of the following:

- Easements, private rights, or other issues created by a recorded subdivision plan

- Municipalities Planning Code or subdivision and land use ordinances

- Land development approval process

DISCLAIMER:

The individuals who provide information for this site work at Sebring & Associates, Attorneys at Law. Any information herein does not constitute legal advice. No attorney-client relationship has been or will be formed by any communication(s) to, from, or as a result of reading this. For legal advice, contact an attorney at Sebring & Associates or an attorney actively practicing in your jurisdiction. Do not send any confidential or privileged information to the writer, as Sebring & Associates assumes no liability or responsibility for it.